Ryan Barnes Seizes the Torch

Chris Barnes’ overflowing trophy case suggests his glory days came in the mid-aughts. The look on his face watching his son Ryan embark on his own PBA career tells a different story.

Amidst the negative-20-degree temperatures that engulfed the Kansas tundra last January, Chris Barnes found solace in nostalgia.

As Barnes strolled around his old stomping grounds, he reminisced on his days at Wichita State University, the longtime collegiate bowling juggernaut.

It was on those very lanes at Bowlero Northrock — and you bet he still has a notepad filled with chicken-scratched observations about the minute pair-to-pair differences — where the former Shocker blossomed into an eventual Hall of Famer and one of the bowling’s all-time greats.

One of just five PBA Rookies of the Year turned Players of the Year and one of just nine Triple Crown winners, Barnes has hoisted a championship trophy 19 times in his illustrious PBA career. After almost two decades on Team USA, his triumphs touch almost every corner of the globe.

Barnes’ days as a weekly title favorite and one of the faces of the tour, however, are long gone. Now in his mid-50s, Barnes is often satisfied with making the first cut.

That was the case one particular week during the 2024 PBA Players Championship.

Barnes, the lone senior player remaining in the field, crossed paths with EJ Tackett, a man 20 years younger with a résumé already superior to Barnes’. Tackett knows what it feels like to walk into every single event as the man to beat.

A feeling once familiar, now foreign to Barnes.

A decade ago, Barnes could have beaten most of his upcoming opponents for round-robin match play in his sleep. But since his back surgery in 2015 — the same one undergone by former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Tony Romo — successes have been few and far between for Barnes.

“My bones are creaking. I don’t know why I continue to do this,” Barnes told Tackett.

“I do,” Tackett said. “Because of that kid right over there.”

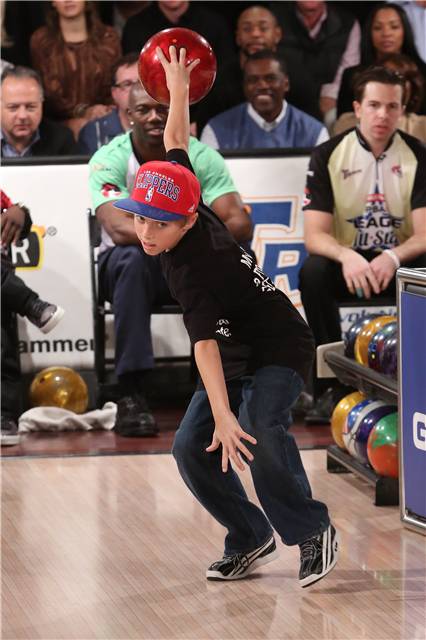

A young Ryan Barnes hurls a one-handed shot during the 2013 PBA CP3 All-Stars event

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

Chris Barnes and Ryan Barnes, father and son, competing together on the PBA Tour was never part of anyone’s plan.

The sons and daughters of many 21st century PBA stars — Justin, Brandon and Sydney Bohn; Kevin McCune; Alyssa Ballard; Jordan Malott; Natalie Kent and so on — have been household names in the bowling community for the better part of the past decade.

Not Ryan. He spent his teenage years on the court, not the lanes.

Once or twice a year, juvenile Ryan would huck a ball down the lane for fun. He said he did have an inclination to compete on tour someday, but only after a 10-plus-year professional basketball career.

During Ryan’s senior year of high school, the sub-six-footer realized the fatal flaw of his hoops ambition. Facing a dearth of college basketball offers and searching for a new challenge to funnel his unyielding competitive spirit, he turned to the family trade.

“When I first picked up a ball,” Ryan said, “I wasn’t really thinking. I was just bowling.”

Even in the teen’s fledgling state, his untapped potential became readily evident to his mother Lynda, a USBC Hall of Famer herself, and Chris.

Ryan’s parents embraced his latest avocation with slight apprehension. They knew what it took to be truly great at the sport; they also knew what sort of expectations would be placed upon their son by the bowling world.

“Would bowling just be one of those hobbies teenagers pick up and abandon?” they wondered. “Or could this game become his future career?”

The Barnes’ soon learned that Ryan, the ever-so-slightly older of their twin boys, was in this for the long haul.

“We went (to practice) for a few days and he wanted to go again and again,” Chris said. “I thought, ‘Alright, we’re really doing this. Let’s go to work.’”

The thing is… when you pick up a sport mere months before high school graduation, college coaches aren’t exactly knocking down your door to offer you a scholarship. The NIL bagmen don’t pay any mind to newbies, let alone those who aren’t 6’5” with an Olympic-caliber standing broad jump.

Not that it would have mattered anyway: Ryan already knew where he wanted to spend his next four years.

On the Kansas prairie, wearing the black and gold, just like his dad.

Ryan Barnes signed to bowl at Wichita State in June 2020

Chris and Lynda, from an athlete’s perspective, knew Wichita was one of the best bowling communities in the U.S. Their instincts as parents differed.

“Why would you go to Wichita?” Lynda said she asked Ryan. “You're never going to get to play.”

Wichita State bowling is akin to Alabama’s football program: If you’re not a five-star recruit, good luck cracking the lineup.

Ryan knew it would take time to earn his keep. Teeming with teenage hubris, he also felt it wouldn’t take as long as others thought.

“I wanted to make the varsity team,” Ryan said. “That was the immediate goal.”

Ahead of his freshman season, Ryan qualified for the developmental (JV) team at Wichita State’s team trials. The varsity team included five past/present/future Junior Team USA members — not including, spoiler alert, Ryan himself — in addition to some of the most decorated youth players in the country.

“Ryan chose to come to Wichita when it was really above his level at the time,” Chris said. “But there's no better place to be, in my opinion. The best bowler at Wichita State is almost never the best bowler in the city. When (Alec) Keplinger was the Collegiate Player of the Year, he could go to Northrock in the afternoon and practice with Packy Hanrahan and François Lavoie. It's one of the best bowling communities in the whole country. There's so much knowledge and so many good ways to get better if you're willing to put in the work.”

During his freshman season, Ryan bowled three tournaments for the JV team. He averaged 189 for his 15 games. He said he practiced every day, turning the eight-lane bowling center inside the campus student center into his dorm room.

Midway through his sophomore season, Ryan earned a permanent promotion to the varsity team after leading an entire tournament field, including varsity players. He averaged more than 215 the rest of the season, notching an NCBCA First Team All-American berth.

Two years after trading in a basketball for a bowling ball, Ryan was an All-American collegiate bowler.

Ryan Barnes (far right) huddles with his Wichita State team during the 2022 PBA Collegiate Invitational

Let’s address the elephant in the room: The Barnes’ connections granted Ryan instant access to some of the best coaching and training available.

Team USA’s training facility in Arlington is about an hour from the Barnes’ home in Denton. Any shred of bowling knowledge unpossessed by mom or dad, of which there are very few, can be answered by a single call or text.

Neither Ryan, nor his parents, would deny Ryan benefited from these privileges. But there are plenty of players with strong genes — bloodlines, if you will — who never became professionals.

The genetic code for sending messengers has yet to be discovered.

“None of it means anything if you don't put in the work and figure out how to apply it,” Chris said.

As Ryan’s talent started to blossom, the nepotism comments inevitably followed. He soon learned to accept, even embrace, chatter from the peanut gallery.

“It’s an unfair advantage for me,” Ryan said. “I don't really see it as pressure or anything like that. If anything, I think it intimidates other people. Imagine bowling against me, and you look back and I'm talking to Chris and Lynda.”

“You can’t teach what they have, and they’re teaching it to me.”

The parallels between one-handed Chris and two-handed Ryan's bowling styles are undeniable

After throttling EJ Tackett in the second game of 2024 PBA Players Championship match play, Chris Barnes took down Chris Via before losing to Boog Krol and Bill O’Neill.

He walked to his next pair and, in signature Barnzy fashion, barked some snarky comment toward his opponent as he set down his bag.

The pain in his back had evaporated and been replaced by an ineffable feeling, perhaps most closely defined as pride.

In the sixth game of match play, EJ Tackett took on Cristian Azcona. Jason Belmonte squared off with Keven Williams. O’Neill went head-to-head with Nate Stubler.

Chris Barnes faced Ryan Barnes.

Ryan Barnes and Chris Barnes chat during their match

Ryan, then a senior at Wichita State, and three of his Shocker teammates were awarded a commissioner’s exemption to bowl the event’s pre-tournament qualifier.

All four proved their mettle and advanced to the main field. All four cashed. Ryan and TJ Rock qualified for match play.

By 2024, the bowling world had caught onto the ascendance of Ryan, now a member of Junior Team USA and a collegiate national champion.

But no one could have foreseen him contending for a PBA major championship so soon.

“I was hoping this would happen someday. I didn't think it would happen by now,” Chris said. “I don't know how much longer I'll be competitive. A chance to bowl against each other in match play of a major, that was a lot of the driving force (this week).”

In one of the rare, but not unprecedented, father-son matches in PBA history, Ryan snuck by Chris with a 195-193 victory.

(The Barnes duo’s low scores during a high-scoring event, they insisted, are explained by the inherent characteristics of lanes 27-28. Ryan’s notes from multiple years of practice and league indicated those lanes are more difficult than most other pairs; Chris’ records and recollections from the 1990s corroborated his son’s observations.)

Not only did Ryan gain ultimate bragging rights over his old man, but he seized 30 bonus pins, which sounds like the type of superficial detail that would overshadow an emotional, transcendent moment unquantifiable by any metric.

While that would be true, those 30 bonus pins were about to offer Ryan much more than mere ammunition to mock Dad at Thanksgiving dinner.

“We both make match play and get to bowl in a match against each other. That was awesome,” Chris said. “And then I realized: Holy crap, he’s going to make the show.”

Chris Barnes overlooks his son, Ryan, as the two face off in match play of the PBA Players Championship

Ryan finished the first round of match play in 15th place. He tallied a 6-2 record during the second round to climb into ninth place, less than 80 pins behind fifth place.

Every time a relative novice like Ryan should have folded, or at least stumbled, he flourished. Even the time when Ryan literally face planted onto the lane — his heel stuck during his slide — he regrouped and made the spare like nothing ever happened.

To start the final round of match play, Ryan needed four strikes in the ninth and 10th frames to shut out Kris Prather. He hamboned without blinking.

“He got that from me,” Lynda said with a smile.

With a berth in the televised finals fully within reach, Ryan averaged more than 243 for his next six games. Heading into a position round match against BJ Moore, Ryan found himself in sixth place and a mere 43 pins outside of the show.

To make the show, Ryan needed to beat Moore by at least 13 pins and hope none of the players beneath him in the standings usurped him. When a disastrous fifth frame from Moore opened the door for Ryan, the relentless and ruthless competitor snatched it.

Chris, himself in 15th place, had already sped through his inconsequential match. Why would he care about a meager difference in prize money when his son was bowling the biggest match of his life 30 feet away?

The veteran has bowled in a hundred of these matches and witnessed a thousand more. None quite like this.

Chris stood a few feet away wearing a matching pink and purple jersey; seldom has the line between parent and competitor been more grey.

Just two strikes lied between Ryan and the show. Unfazed by the hoard of cameras and undaunted by the magnitude of the moment, he labeled three strikes for good measure.

Ryan celebrated with a fist pump, walked off the approach and hugged his father. No words were exchanged; there didn’t need to be.

“He did it in the best way, the one we always dream about,” Chris said. “Whether it's basketball or baseball, you want to step up and make the big shot to make it. That's the dream come true as a competitor. As a parent, it hits different. That's all I can say.”

Critics could boil Chris’ entire Hall of Fame career down to shortcomings on TV. The meticulous nerd owns 19 PBA Tour titles; a more carefree competitor, those detractors would argue, might have won another dozen.

Chris has served many roles during PBA shows, from fan to player to color commentator to coach. Dad would be a new one, though.

“I thought it was interesting watching Chris and how nervous he was,” Lynda said. “Standing next to him, I could feel it. He made me more nervous than anything because he wanted it for Ryan so much. He was second guessing himself: ‘Did I give them the right information? Am I doing the right thing?’”

“But really it's in Ryan's hands,” Lynda continued. “Ryan is going to do what Ryan does.”

Lynda overlooks an emotional Chris as Ryan prepares to shoot a spare

What Ryan does is the singular thing that Chris never could: turn off his brain.

“That’s the trick I don’t have. I’m envious of it,” Chris said. “He wasn’t overthinking the process. That’s when I thought this could get real fun today.”

With his mom and dad sitting behind him and his entire college team to his left, Ryan started off perfect. Five frames. Five strikes.

“In the fifth frame, Ryan just dead-labeled it and I almost burst into tears,” Lynda said. “I've watched Chris bowl a thousand times and I've never felt like that. I was just so proud of how (Ryan) was managing his emotions and taking care of business. I was overwhelmed by the whole thing and I had to get myself together for him.”

During his 267-223 first win over Chris Via and narrow 224-220 win over Nate Stubler, a recent graduate of Wichita State-rival St. Ambrose University, Ryan relished the hometown atmosphere.

Ryan's Wichita State coaches and teammates celebrate a strike

“I knew I had all my guys right there,” Ryan said. "I was just trying to take advantage of that. I was trying to talk trash today and get in other people’s heads a little bit.

“I mean, I did.”

A Brooklyn strike from Bill O’Neill in the ninth frame ended Ryan’s poetic run in the semifinal match.

(Please use that link and watch Chris’ reaction in the background. It’s the funniest thing you’ll see all day.)

The rookie made the switch from urethane to reactive a couple frames too late and O’Neill, using a trick he once learned from Chris himself, went on to win the tournament.

But Ryan won the day.

Ryan thanks the crowd after his last shot of the 2024 PBA Players Championship finals

Twenty-seven years after Chris earned PBA Rookie of the Year honors, his son will be a favorite for the same honor.

Ryan Barnes, the kid who never envisioned a bowling career, will be an exempt, full-time touring player in 2025.

Ryan joined the PBA after graduating in May and spent the rest of the year competing in the PBA Southwest Region. He racked up six top-10 finishes in eight events and earned the region’s Rookie of the Year award.

“People in the bowling world (look at me differently now),” Ryan said last summer. “I gained a little bit of people's respect. I stopped becoming just Chris Barnes and Lynda Barnes’ son.”

In August’s PBA Tour Trials, Ryan secured an exempt berth on the 2025 PBA Tour. In January 2025, he won Team USA Trials, securing his first berth on the team his father presided over for two decades.

“From the beginning, I wanted to get to this level,” Ryan said. “It's like a dream because everything's going, I want to say, as planned. You make a TV show before you're (on tour), then you come out to Tour Trials and make it out. I'm just really excited to bowl against these guys in January.”

Among those competitors will be Chris himself. The living legend is no longer an exempt player, but his résumé will grant him priority entry into most, if not all, events.

Entry fees are a mere pittance to pay to be alongside your son’s budding professional bowling career.

“He's reinvigorated my desire to be out here and share some of that early part as he makes his way,” Chris said. “I can't wait to watch what happens next for him. Hopefully I’m around and get to enjoy it along with him versus just watching, but either way I'm excited for him. I hope he goes by every achievement that I was lucky enough to get.”

“The kid doesn’t know failure,” Lynda said. “And I hope he never does.”